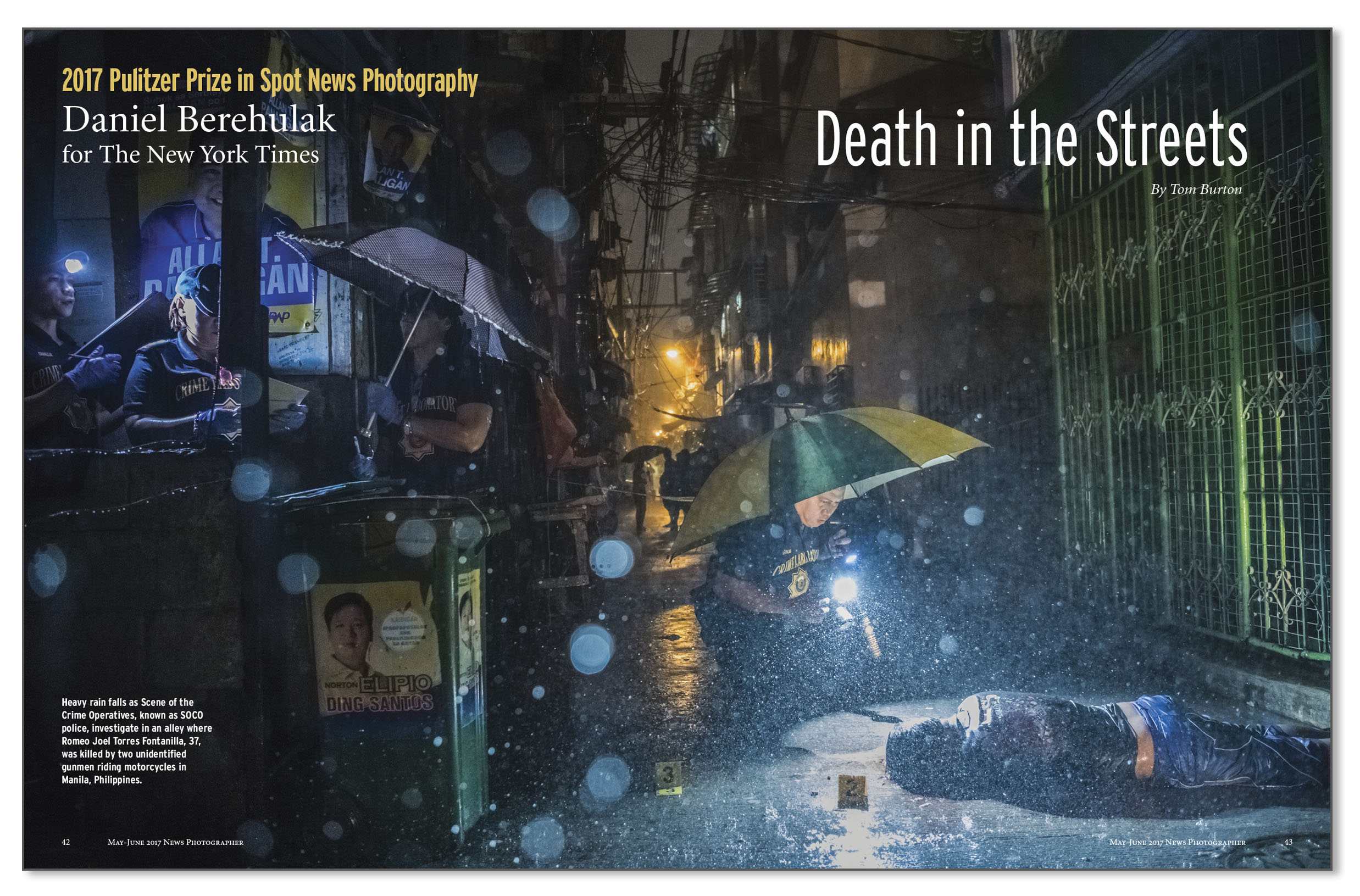

‘They are Slaughtering Us Like Animals’

Daniel Berehulak’s wide-reaching and disturbing photo story of the mass killings of Filipinos in a “war” on drugs

By Tom Burton

The girl’s body had landed on a trash pile. Even in the context of the nightly terror in and around Manila, Philippines, that has led to thousands killed, this murder scene was especially disturbing. Daniel Berehulak made photos and took notes. A bystander, too afraid to share his name, guttered a despondent assessment:

“They are slaughtering us like animals."

The girl in the street was Erika Angel Fernandez, 17. She and her boyfriend, Jericho Camitan, 23, had been gunned down by masked men in the early morning hours.

They were two of thousands killed as part of a brutal and indiscriminate campaign against drugs directed by Filipino President Rodrigo Duterte. who took office last June. When Berehulak’s story was published in The New York Times in December 2016, the newspaper reported that police had killed 2,000 people. Duterte gave the veiled threat that 20,000 to 30,000 more could meet the same fate. An additional 3,500 unsolved homicides were on the books, believed to be the work of vigilantes. More than 35,000 have been arrested.

The bystander’s quote became the headline for the story in the Times that won the 2017 Pulitzer Prize for Breaking News Photography. An independent photographer based in Mexico City, Berehulak previously won the 2015 Pulitzer Prize for Feature Photography for his coverage of the Ebola outbreak in Africa, also on assignment for The New York Times. In 2011 while on staff for Getty Images, he and Paula Bronstein were finalists for the Pulitzer Prize in Breaking News Photography for coverage of flooding in Pakistan.

The Philippines assignment began with Berehulak’s talking to David Furst, his editor at the Times, when news began to come out that Duterte was serious about his campaign promises to mount a harsh crackdown on drug users. Furst was interested, and they waited for the right timing. When Berehulak’s visa application fell through for an assignment in Syria, the photographer’s schedule opened up.

Berehulak spent 35 days in the Philippines, based out of Manila. In that time, he covered 41 crime scenes where 57 people had been killed. In one house alone, there were five bodies. He worked every day, starting about 9 p.m., because most killings happened overnight. He followed up with witnesses and families during the day to find their side of the stories about the killings. The shootings were so constant, Berehulak was always working, pulling at least one 36-hour shift.

Even with his career experience in more than 60 countries covering a wide range of crisis stories, Berehulak said the assignment in the Philippines was one of his most difficult.

“It was different because it was an urban environment,” Berehulak said. “It wasn’t war. It wasn’t a virus. It was a fully functioning city.”

Berehulak started his photography career covering sports in Australia, his home country. He eventually joined the Getty Images staff. He had majored in history in college and wanted to travel and see the places he had studied. So after a few years, he transferred to the London office in 2005. He moved to the New Delhi bureau in 2009.

By 2013, he went freelance so he could have more control over his work. Until then, the copyright on all his work had been owned by his employers.

“I thought it was important that before I die, to own at least one image,” Berehulak said.

When he arrived in the Philippines, Berehulak didn’t know for about a week whether there would also be a writer on the story. When it was decided he’d be working on his own, he started gathering even more information for captions, including recording audio interviews.

He also hired Rica Concepcion, a Filipina journalist with 30 years of experience, to work with him.

“It is crucial for us to be working with someone who is local,” Berehulak said of journalists who come into another country, especially in dangerous situations. Local journalists understand the dynamics of the story and help the visitors to work safely and respectfully. Without Concepcion’s contributions, Berehulak said, his reporting would have been limited.

Each night, the pair started at the district police headquarters in Manila. Journalists would form a convoy, going to crime scenes as shootings were reported. It was always busy. During Berehulak’s stay, there was an average of 24 killings a day.

Though the streets were deadly, the journalists did not feel that they were targets and thus were relatively safe. The police were cooperative and were often happy to display their efficiency and call to action.

“They felt that they were doing the right thing,” Berehulak said.

After long and intense nights covering the killings, the journalists would get breakfast as the sun came up, decompress together and share resources. During daylight hours, they would go their own ways to follow up with families and neighbors for those stories.

Berehulak was making a lot of pictures. He worked continuously because he didn’t know when the assignment would end and whether he had two more days or two more weeks to work. Each day, he would copy his disks onto both a main drive and a backup drive that he would keep in a safe. He made sure the photos had caption information and accurate metadata to make it easier to match images with stories when he started editing.

When he finally left Manila, Berehulak had made about 25,000 images to be edited. He cut that take down to a rough edit of 800 images, then to 306 that were fully edited. The final story is 21 photos.

Editing at home proved to be even more difficult psychologically than when Berehulak was making the photos on the streets. With the urgency of working quickly, the camera in his hand could function as an emotional buffer for Berehulak. He didn’t have that filter when he was reviewing his photos.

“Editing is the second round. It is a struggle to look at most of those images,” Berehulak said. He admits being depressed through those weeks, alone in his apartment. “It was crippling.”

The toughest moment for him, both when he made the photo and then during the edit, was covering the funeral of Jimboy Bolasa. The photo shows a funeral home, saturated by red light, showing Bolasa’s 6-year-old daughter, Jimji, crying out over the open casket. She screamed, “Papa! Papa!”

Berehulak had 12 images from that sequence and believes that three or four of them could have been the final choice. He reviewed them repeatedly, reliving the scene and hearing in his mind the child’s sobbing.

When the story published in December, the reaction was immediate and widespread. Berehulak was in Cambodia at the time, and his email and social media started filling up. He often receives feedback from within the photojournalism community when his stories are published, but this time it also came from the general public, who were stunned by this story, of which many had not been aware.

There was also negative feedback. He was targeted online by Duterte supporters, received death threats, and his Facebook account was hacked. The trolls eventually slowed down but kicked back in when the Pulitzer was announced. There were even fake stories that said Berehulak had set up photos or had used filters on his cameras to dramatically change the lighting. They falsely reported that he had returned to the Philippines on assignment and had been robbed at gunpoint by the drug dealers he was “sympathetic” to.

The story in the Times sparked more in-depth coverage in the Filipino media. International criticism of the extrajudicial killings grew, but the Duterte administration and the police claimed that the death toll numbers were exaggerated and are “alternative facts.”

As this siege continued in the Philippines, Berehulak admited that journalists covering the story can at times feel helpless. They questioned whether they were making a difference. Berehulak felt the work mattered.

“What we were doing was gathering evidence,” Berehulak said. He believed that the stories journalists told of the families and victims would stand as proof that the police version of the drug crackdown was wrong.

“It was outright murder, and state-sanctioned murder,” Berehulak said.

A version of this story originally appeared in the May/June 2017 issue of News Photographer magazine.

President Rodrigo Duarte’s “War on Drugs” continued through the end of his presidency in 2022. Human rights organizations and academics estimate that national police and vigilantes killed between 13,000 and 30,000 people. Duarte was arrested in 2025 on a warrant from the International Criminal Court (ICC), charged with the crime against humanity of murder in relation to killings.